I note briefly that MacDonald's opening comments about how the music of poetry is its garment, the thing we first perceive as the poem reveals Truth to us, reminds me of his discussion of nature, of Creation itself. Our immediate perception of the beauty of a rainbow leads us on to a Truth about God, the Master Poet Himself. And, with respect to the fifth verse of The Elixir, one immediately thinks of MacDonald's references to obeying the Lord in the simplest of actions, such as sweeping a floor; an image that might well have stuck in his mind from reading this poem of George Herbert.

From Chapter XIII of England's Antiphon:

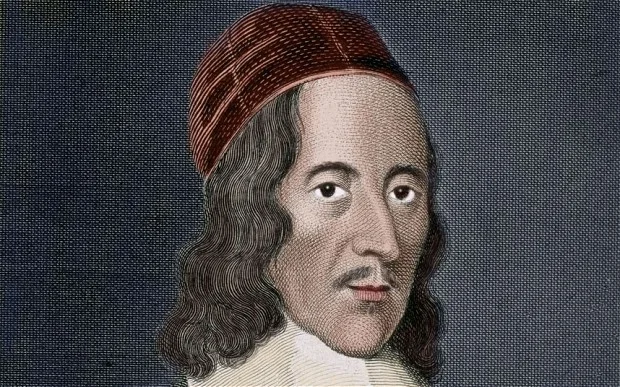

In George Herbert there is poetry enough and to spare: it is the household bread of his being. If I begin with that which first in the nature of things ought to be demanded of a poet, namely, Truth, Revelation -- George Herbert offers us measure pressed down and running over. But let me speak first of that which first in time or order of appearance we demand of a poet, namely music. For inasmuch as verse is for the ear, not for the eye, we demand a good hearing first. Let no one undervalue it. The heart of poetry is indeed truth, but its garments are music, and the garments come first in the process of revelation. The music of a poem is its meaning in sound as distinguished from word -- its meaning in solution, as it were, uncrystallized by articulation. The music goes before the fuller revelation, preparing its way. The sound of a verse is the harbinger of the truth contained therein. If it be a right poem, this will be true. Herein Herbert excels. It will be found impossible to separate the music of his words from the music of the ghought which takes shape in their sound.

I got me flowers to strow thy way,

I got me boughs off many a tree;

But thou wast up by break of day,

And brought'st thy sweets along with thee.

And the gift it enwraps at once and reveals is, I have said, truth of the deepest. Hear this song of divine service. In every song he sings a spiritual fact will be found its fundamental life, although I may quote this or that merely to illustrate some peculiarity of mode.

The Elixir was an imagined liquid sought by the old physical investigators, in order that by its means they might turn every common metal into gold, a pursuit not quite so absurd as it has since appeared. They called this something, when regarded as a solid, the Philosopher's Stone. In the poem it is also called a tincture.

The Elixir

Teach me, my God and King,

In all things thee to see;

And what I do in any thing,

To do it as for thee;

Not rudely, as a beast,

To run into an action;

But still to make thee prepossest,

And give it his perfection.

A man that looks on glass,

On it may stay his eye;

Or if he pleaseth, through it pass,

And then the heaven spy.

All may of thee partake:

Nothing can be so mean,

Which with his tincture--for thy sake--

Will not grow bright and clean.

A servant with this clause

Makes drudgery divine:

Who sweeps a room, as for thy laws,

Makes that and th’ action fine.

This is the famous stone

That turneth all to gold;

For that which God doth touch and own

Cannot for less be told.

England's Antiphon can be purchased in beautiful cloth cover from Johannesen Publishing.

The edition of Herbert below has a special place on my bookshelf: